JULY 2025

Featured

JUNE 2025

Featured

MAY 2025

Featured

APRIL 2025

Featured

MARCH 2025

Featured

FEBRUARY 2025

Featured

JANUARY 2025

Featured

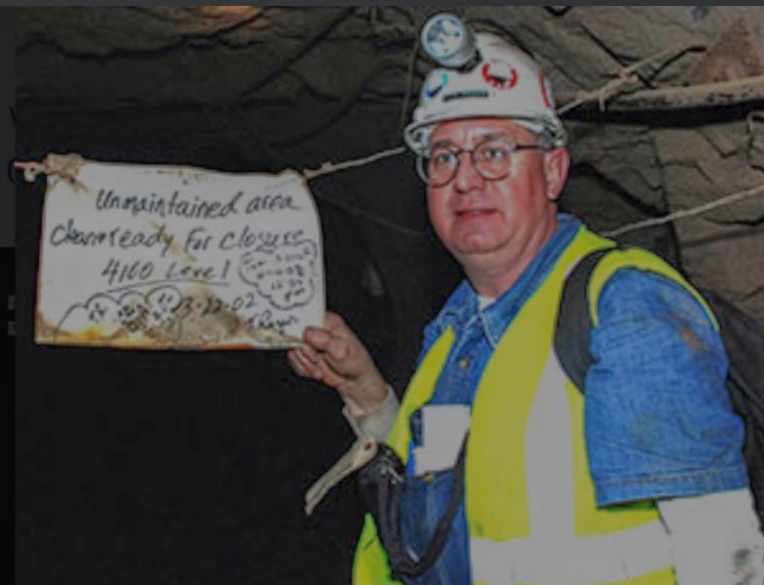

Tom Regan

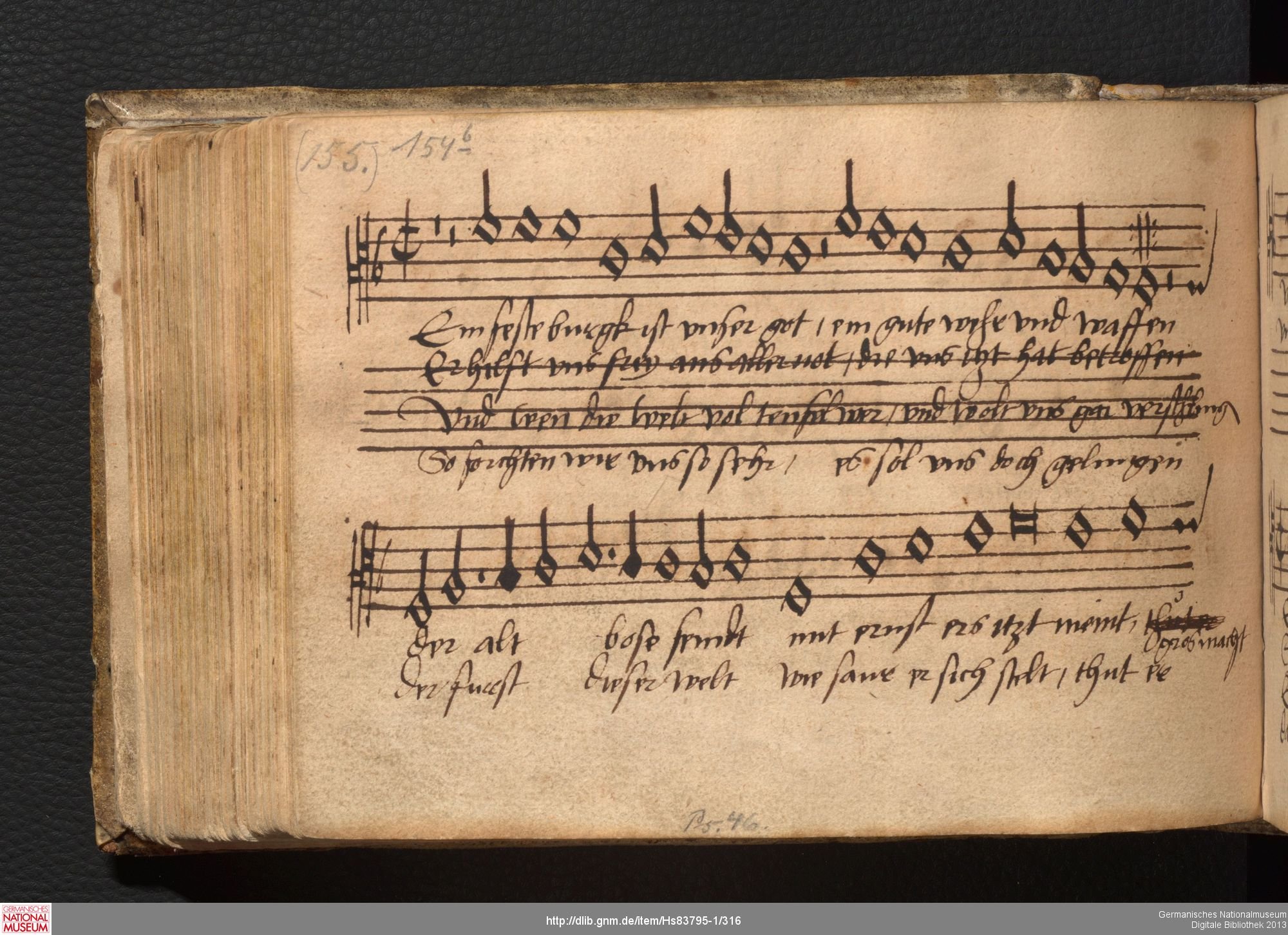

IMMORTAL, INVISIBLE, GOD ONLY WISE

Tom Regan

Tom Regan