RECONSIDERING THE ARTICLES OF RELIGION: WHAT DO THE ARTICLES TEACH?

Early edition of the Articles of Religion, Corpus Christi College. Public domain.

In 1585, the Rev. Mr. Thomas Rogers, incumbent of the parish of Horringer in Suffolk, published a work entitled The English Creede. This work, which would go through some ten editions between 1585 and 1639, was a comprehensive defense of the doctrinal position of the Church of England. In this book Rogers defended the teaching of the Church of England by showing its conformity to Scripture, the early church, and the confessions of other Protestant churches. And where did Rogers look for the teaching of the Church of England? The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. As he put it in the new preface to the substantially revised 1607 edition, “The purpose of our Church is best knowne by the Doctrine which shee doth professe; the Doctrine by the 39. Articles, established by Act of Parliament.” That is to say, for Thomas Rogers, the Church of England had a clear confession, and that confession was the Articles of Religion.

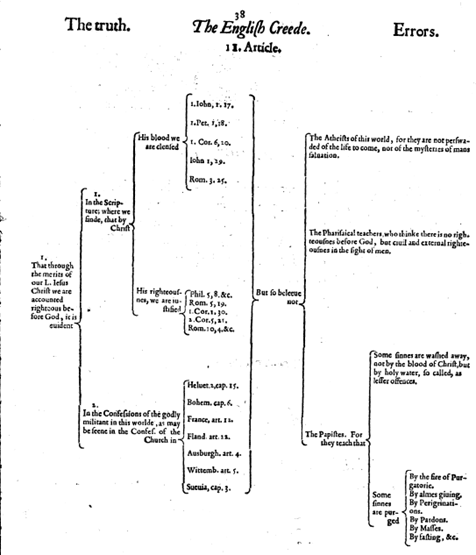

Rogers’ treatment of the first part of Article XI (“Of the Justification of Man”) in the first edition of The English Creede. Note the use of Ramist diagrams (logical tools developed by the Huguenot philosopher Petrus Ramus).

The existence and popularity of a book like Rogers’ challenges a well-worn narrative about the history of Anglicanism that suggests that Anglicanism was never ‘confessional.’ The Protestant churches of Scotland and the continent may have produced extensive and binding confessional standards – as indeed did Roman Catholicism – but Anglicanism was, on this argument, different. Sometimes it is argued that Anglicanism preferred to locate its doctrinal unity in the creeds shared by all Christians rather in anything specifically Anglican, a sort of doctrinal credal minimalism. Other times it is argued that the unity of Anglicanism was never grounded in shared belief at all so much as shared worship. Either way, talking about confessional Anglicanism is taken to be a contradiction in terms, and any notion that the Articles of Religion had a confessional status is seen as the product of wishful thinking by eighteenth century (or twenty-first century) evangelicals.

Take, for example, the entry on the Thirty-Nine Articles in Don Armentrout and Robert Slocum’s An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church, given a sort of quasi-official status by its placement on the Episcopal Church’s website: “The Articles are not a creed nor are they a confessional statement such as those produced by the churches of the Reformation. They seek only to provide a basic consensus on disputed points and to separate the Church of England from certain Roman Catholic doctrines which were regarded as medieval abuses or superstitions.” Or the introduction to the Articles of Religion in the website of the Anglican Church of Canada, which declares that they “have never been officially adopted as a formal confession of faith in any province of the Anglican Communion, but they serve as a window onto the theological concerns of the reformed English church.”

This argument about the nonconfessional nature of Anglicanism is typically simultaneously historical and normative. That is, there is a claim made about the Anglican past, that there was never a period in which Anglicanism was ‘confessional’ or the Articles were the Anglican ‘confession.’ This historical claim is then generally used to advance a nonconfessional approach to Anglicanism today in which the Articles play no significant role. But I just don’t think this reading of Anglican history is accurate. And I am not convinced that this normative approach to Anglicanism identity today is what we need. And so, I’m going to tackle this question of the Articles in Anglican history and for contemporary life in three separate pieces. I’ll begin today with a brief introduction to the Articles of Religion. The next piece will treat the place of the Articles in the history of the Church of England and Anglicanism broadly and argue that they very much did function as the Anglican confession well into the twentieth century. I’ll finish in the last piece by turning to a normative claim of my own: not only were the Articles our historic confession, but they have promise today too for articulating an account of Anglican belief that sets forth the good news of Jesus Christ to a needy world.

What Are the Articles of Religion?

For today, my focus will be on providing a brief overview of the Articles. I think this is important because it seems to me that they are so often treated as an identity marker to be fought over that we don’t actually pay much attention to what they are. That is, before we think about what their place has been in Anglican history or what their place should be today, it’s important that we think about what they have to tell us about Jesus, salvation, the church, sacraments, and so on. So, what are they? The Thirty-Nine Articles are a statement of faith put forward in the reign of Elizabeth I in 1563, arriving at their final published form in 1571. Although they followed several earlier statements of faith and faced significant political headwinds early in its history, it was these Articles (largely based upon an earlier doctrinal statement of the early 1550s) which would define the doctrinal position of the Church of England through Elizabeth’s reign and beyond.

The first five articles deal with the basics of Trinitarian and Christological orthodoxy: the doctrine of the Trinity (Art 1), Christology (Arts 2-4), and pneumatology (Art 5). There is nothing here that any orthodox Western Christian couldn’t agree with. The next three deal with Scripture (Arts 6-7) and the creeds (Art 8). Here we start to see a distinctly (although fairly non-polemical) Protestantism emerge: the Articles assert that “Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation,” diminishes the authority of the Apocrypha, and defends the creeds not on the grounds of conciliar authority or the long-standing tradition of their use but because they are grounded in Scripture.

Articles 9-18 then deal with salvation, the core theological issue of the sixteenth-century Reformation. And here the Articles take a firm but broad Protestant line. They assert that humankind is so wholly captive to sin that we cannot deliver ourselves or in any way merit salvation (even by the help of God’s grace). Rather, we are saved solely by God’s activity, by Jesus’ death and merit which becomes ours through faith. The Christian is to respond to the free gift of salvation through good works, but these works always remain imperfect. Predestination is affirmed, but with reserve: what is important is to emphasize God’s power in salvation, not peer into the secret counsels of God. This is all teaching about which a sixteenth century Reformed or Lutheran thinker could agree.

Those who are familiar with later developments in the confessional standards of the Reformed tradition might notice some things that seem missing here: there’s no explicit discussion of reprobation or predestination to damnation (that God not only actively chooses to save some but also actively chooses to damn others), the question of whether it’s possible to fall away from faith, whether Christ died for all people or only for the elect, and so on. Their absence does not prove that the Articles are somehow ‘un-Reformed.’ Rather, this absence simply reflects the context in which the Articles were put forward. Recall that the Articles were put forth in 1563 and based on a document from a decade earlier. The sorts of questions that roiled the Reformed world about questions like the extent of the atonement or the resistibility of grace simply had not become major areas of contention, nor had double predestination become a significant marker of Reformed identity. Indeed, other Reformed confessions put out around the same period like the Scots Confession (1560) and the Second Helvetic Confession (1566) similarly do not find it necessary to mention these questions, although brief discussions of reprobation do occur in the French (1559) and Belgic (1561) confessions.

If the Articles’ treatment of salvation is broadly Protestant, the next section on the church and sacraments (Articles 19-34) strike some distinctly Reformed notes. To be sure, there’s a lot here that any Protestant could agree with, but the treatment of the Lord’s Supper in particular takes the Reformed position on the key Lutheran-Reformed area of controversy. Nowhere is this clearer than in Article 29, “Of the Wicked which eat not the Body of Christ in the use of the Lord’s Supper.” As the title suggests, this article asserts with the Reformed and against the Lutherans that the wicked and faithless do not actually receive Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper, but merely the signs of Christ’s body and blood. This does not mean that Christ’s body and blood are not involved in the Supper. In fact, Article 28 asserts that they are given, taken, and received in it. But it does rule out some ways of construing the manner of that involvement. This article was so clearly anti-Lutheran that Elizabeth did not allow it to be published in 1563; in 1571, as hopes for an alliance with Lutheran powers dimmed, Elizabeth allowed it to be made public.

Articles 35 and 36 then affirm the value of the Books of Homilies (two sets of authorized sermons, one put out in the reign of Edward and one in the reign of Elizabeth) and the Ordinal (the liturgies for the ordination of bishops, priests, and deacons) . The final three articles (Arts 37-39) deal with questions of civil order and the magistrate, condemning a variety of Anabaptist as well as Roman Catholic views.

To sum up, then, the Articles lay claim to common Christian orthodoxy on Christology and the Trinity as expressed by the Western Church. They defend a broadly Protestant account of Scripture, salvation, and the church without reference to later Reformed disputes about salvation or a hard-edged double-predestinarianism. They take the Reformed line on the sacramental questions that divided the Reformed from Lutherans. They oppose both Roman Catholic and Anabaptist construals of the church and its relationship to civil order. In short, they comprise a generous (at least for the period!) but clearly Reformed statement of faith.