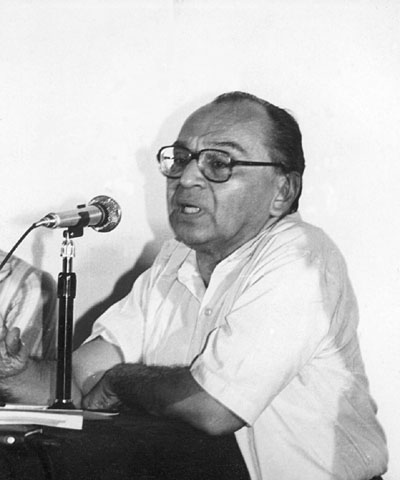

WHO IS GUSTAVO GUTIERREZ?

Public domain.

Gustavo Gutiérrez (b.1928) is widely known as the father of liberation theology. His thought was first presented in A Theology of Liberation in 1973 (1) (originally, Teología de la liberación: Perspectivas, published in 1971). After a brief biography, I will turn to Gutiérrez’s central ideas before tracing them through the tradition that arises from him, as well as the critiques levied by the Roman Catholic authorities and other liberationists after him.

Gutiérrez was born in Peru in 1928 to an indigenous parent as well as one of European descent. He experienced a long-term childhood illness that ultimately helped him discern his vocation to the priesthood. He went to Europe for his philosophical and theological formation like most priests of his time (training at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and the University of Lyon in France). There he was exposed to contemporary philosophical and theological thought – phenomenology, existentialism, Marxism, social theory, and the work of Edward Schillebeeckx (a major influence on the Second Vatican Council), as well as other theologians who were taking an “anthropological turn,” i.e., valuing human experience as a source of revelation in addition to Scripture and Tradition.

Gutiérrez returned to Latin America to minister and work as a priest, at a parish in Rimac, Peru – a poor area that still has slum housing on its outskirts. In 1974, he founded a branch of an organization that works alongside the poor, advocating and organizing: the Bartolomé de Las Casas Institute. He reflects later in life that the poor taught him how hope persists in spite of suffering. (2) His European studies expanded his horizons, but he grounded his thought in the attempt to understand the poor in Peru and the rest of Latin America. As he worked directly with the poor, he continued to develop his thinking, culminating in A Theology of Liberation. Here, Gutiérrez expounds the idea of God’s ‘preferential option for the poor.’ (3) Gutiérrez argues that God is on the side of the oppressed, whom he often (although not exclusively) associates with those living in material poverty. Of central importance is the Exodus narrative, where God liberates God’s people from slavery. It could be said that for Gutiérrez and other liberation theologians, Scripture begins in Exodus 3 when God reveals Godself to Moses, seeking the liberation of God’s people. Scripture is the witness of God’s siding with the oppressed for their liberation, in contradistinction to their ‘development,’ which perpetuates the capitalistic system of exploitation and oppression.

Another central aspect of Gutiérrez’s thought regards history and its relationship to theology and revelation. For Gutiérrez, theology reflects on history: “Theology is reflection, a critical attitude. Theology follows; it is the second step.” (4) Theology does not build a metaphysical system that phenomena of the world subsequently fit into, as systematic theologians might attempt (e.g., Thomas Aquinas or Saint Augustine). Rather, the theologian engages with situations in the world (particularly, being alongside and with the situations of the poor) and reflects on them to discern what God is doing and wants to do. We are not confined to history, however. Gutiérrez argues that “[t]he present in the praxis of liberation, in its deepest dimension, is pregnant with the future; hope must be an inherent part of our present commitment in history. Theology does not initiate this future which exists in the present…It interprets and explains.” (5) It is praxis which initiates this future, the Church’s work and mission in the world. Alongside liberation theology was the development of ecclesial base communities – small groups of people living and working together, reflecting together on the Scriptures and the life of the Church to empower themselves towards liberation. It is these groups that make theology possible, and do so by doing theology together.

It is easy to quickly associate this future with a Marxist understanding of utopia – the classless society at the end of materialist dialectic. This is doubly so since Gutiérrez uses Marxist analysis, but for Gutiérrez (and liberation theology), the utopia in which the poor will be liberated and the exploitation wrought by capitalism will cease is the Reign of God. (6) For Gutiérrez, this liberation is not the end of a dialectical process, but the faithfulness and the drive of the God of the Exodus – God hears the cry of the poor and works to liberate them. The people of God must also work for the liberation of the poor in order to know and serve God (a liberationist reading of Matthew 25’s parable of the sheep and the goats). As Gutiérrez writes, “To accept poverty and injustice is to fall back into the conditions of servitude which existed before the liberation from Egypt. It is to retrogress.” (7) God works to liberate the people of God, to free them from poverty, oppression, and slavery. This utopia which drives the analysis is the vision of the effective presence of God, who is love and freedom, filling the entire cosmos. It is the vision of the New Jerusalem. Until this is inaugurated, the people of God take material, historical actions to bring about more liberation, following the call and movement of God. Gutiérrez summarizes it succinctly: “To be with the oppressed is to be against the oppressor.” (8)

While never officially censured, Gutiérrez was severely scrutinized by Pope John Paul II, who was very critical of the use of Marxist analysis in Latin American liberation theology, given his own Polish context of Stalinist oppression. (9) Liberation theology, however, was largely supported by the bishops in South and Central America, particularly in name, as well as in concept and work, at the Puebla Conference in 1979. The early Medellín Conference in 1968 was a foretaste of liberation theology’s thrust, inspiring both Gutiérrez as well as the later Pope Francis; here, the bishops agree that the Church should be “a poor church for the poor.” Following Puebla, a whole cadre of liberation theologians began writing and publishing in earnest following Gutiérrez, including Jon Sobrino, Leonardo and Clovidus Boff, Igancio Ellacuría, and many others. (10) An excellent and well-developed primer of Latin American liberation theology is Mysterium Liberationis edited by Sobrino and Ellacuría (before his martyrdom).

Beyond Latin America, liberation theology from Gutiérrez has been influential for most contextual theologies (11) developed from the 1970s onwards, including Black, Queer, Feminist, and Eco. While each contains a critique of the origins of liberation theology (e.g., it is not sufficiently critical of racism, is too heteronormative, is not critical of gender oppression, or does not recognize the matrix between material poverty and ecological vulnerability), each furthers the liberationist impetus to challenge history with a better future – a utopian vision of the Reign of God or the “kin-dom” of God. These ways of challenging and deepening liberation theology continue to further what Gutiérrez acknowledges was the questions of liberation theology: “To speak about a theology of liberation is to seek an answer to the following question: what relation is there between salvation and the historical process of human liberation?” (12) This is the question that even today is not yet fully answered. Economic oppression still exists across the world, incomes inequality exacerbates issues of power between peoples, persons are still persecuted because of their gender or sexual identity, ecological injustice is rampant, and the color of people’s skin still conditions their place in many (if not all) societies. The work of liberation and liberation theology continues on – reflecting on the experiences of the oppressed and working towards the fullness of life for all people, the coming of the Reign of God.

The revised version appeared as Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation, trans. and eds. Sister Caridad Inda and John Eagleson, (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1988).

Daniel Hartnett, (3 February 2003), "Remembering the Poor: An Interview With Gustavo Gutiérrez". americanmagazine.org. America Magazine. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

While this is present throughout A Theology of Liberation, for a concise defence of this, see Gutierrez’s essay, “Option for the Poor,” in Mysterium Liberationis, (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1993), pp.235-250).

A Theology of Liberation, p.9.

A Theology of Liberation, pp.11-12.

For two excellent essays on Marxism and the concept of utopia, see Mysterium Liberationis, eds. Jon Sobrino and Ignacio Ellacuría, (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1993): Enrique D. Dussel’s “Theology of Liberation and Marxism” (pp.85-103) and Ellacuría’s “Utopia and Prophecy in Latin America” (pp.289-328).

A Theology of Liberation, p.165.

A Theology of Liberation, p.173.

For the most sustained critique from official Vatican sources, see Joseph Ratzinger, The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church, (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1985).

Whether one counts Archbishop Oscar Romero in this list is a question. He was, nonetheless, supportive.

Contextual theologies are most straightforwardly defined as theologies that take human experience as essential to revelation. We know God in and through our experiences, as well as through Scripture and tradition (both of which presuppose human experience). Therefore, when we construct our theological method or system, the contexts of our experiences must be in play – whether we acknowledge them or not, i.e., the contextual theologian would argue that all theology is contextual, including systematic theology. Gutiérrez makes this point in the Hartnett interview.

A Theology of Liberation, p.29.