NOTHING BUT THE BLOOD

What can wash away my sin?

Nothing but the Blood of Jesus.

Robert Lowry’s “Nothing But the Blood of Jesus” was first introduced at a New Jersey Baptist camp meeting in 1876, where “this very simple hymn … immediately took possession of the people.” (1)

It is easy to see why. “Nothing But the Blood of Jesus” is indeed a very simple hymn. It is easy to learn and has rich lyrics. Like other gospel hymns, it has a single, clear, straightforward theme: the saving power of the sacrificial blood of Jesus.

In this, it occupies a place alongside other classic gospel “blood hymns” from this revival tradition such as “There’s Power in the Blood” and “Are You Washed in The Blood?”. Like these two other hymns, “Nothing But the Blood of Jesus” strongly focuses on Christ’s Blood as something that washes away sin (“what can cleanse me from my sin?”) and frees us from sin’s consequences (“for my pardon this I plea”), often understood in a legal, juridical sense. The shedding of Christ’s Blood in his death on the Cross, in this view, uniquely fulfills the debt incurred by sin that otherwise demanded our own death and blood.

That’s how I was taught to understand “Nothing But the Blood of Jesus” when I first learned it in the fourth grade. Using transparency sheets on the overhead projector, the teacher drew diagrams explaining how the Cross bridges God and “Man” across the separating chasm of Sin, and gets us off the hook from the divine punishment by absorbing and satisfying the Father’s violent wrath in our stead. In order to redeem this benefit and escape everlasting Hell, I needed to make an individual choice to ask Jesus into our heart as my personal Lord and Savior, putting faith in his blood shed for my offenses that I may be washed “white as snow”. This was the meaning of the hymn, I gathered.

Now in my late twenties, much has changed in my own faith. The kind of Christian communities I live and serve in are quite different from the ones which first nurtured and formed my faith. My own theological commitments have changed significantly. I’m now an Episcopalian — and a priest, too.

Yet all these years later, the Blood of Jesus is still vivid in my theological imagination, strange and captivating.

However, it speaks to me differently. No longer do I see the Blood of Jesus mainly as a sort of infinite bail for my soul, or a spillage resulting from the Son suffering capital punishment that the Father had slated for us (however understood). Now, when I think of the blood of Jesus, I still do see him offering his life on the Cross. But then, through the haze of incense, I also see a full chalice, elevated above the altar by the priest for me to see and adore. And I see it presented to me with great reverence and care as I kneel at the Communion rail in awe beside my fellow siblings in Christ.

“The Blood of Christ, the Cup of Salvation,”

“The Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, which was given for thee, preserve thy body and soul unto everlasting life.”

Since becoming an Anglican, I’ve often found it difficult to bridge this understanding and image of the blood of Christ with the one of my childhood, the one also assumed and expressed by “Nothing But The Blood”. Sure, I might be able to trace theological and historical connections between them, but at the level of the heart — devotionally and affectively — they have felt worlds apart.

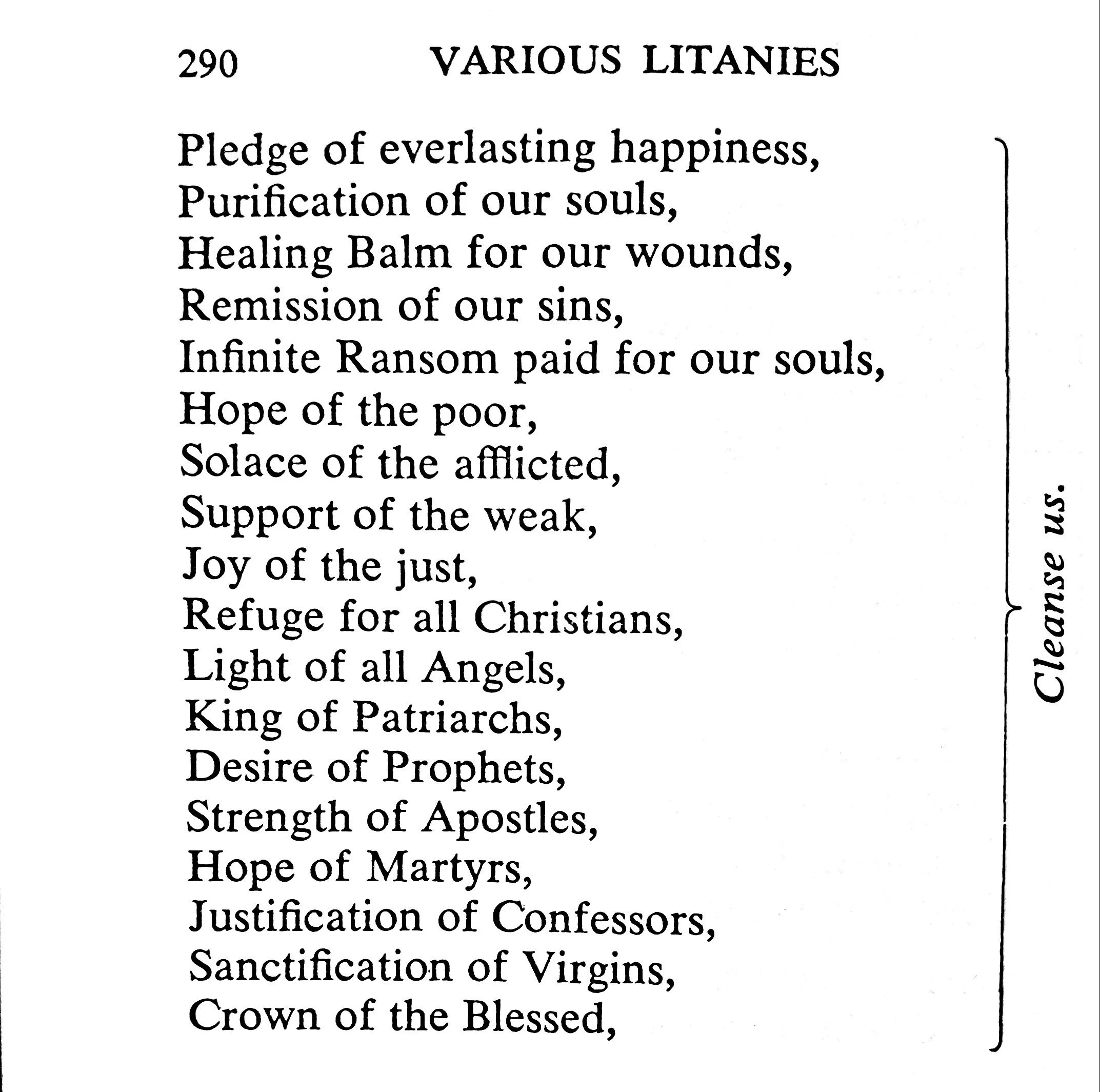

Recently, I’ve been intentionally revisiting the devotional world of my childhood in order to see what from it might speak to my current spirituality in new ways. One day, while flipping through my copy of the widely-beloved Anglo-Catholic devotional manual, Saint Augustine’s Prayer Book, I came upon the Litany of the Precious Blood, a traditional devotion that praises Jesus in a special aspect of himself as God incarnate — his blood. (2)

And as I prayed this litany, I found that “Nothing But The Blood” entered my consciousness — I realized that it bears some striking similarities to a Litany of the Precious Blood. Here’s a short selection:

Like this litany (or any litany in general), Sankey’s hymn has a repetitive, list-like structure. It has a series of statements (or in verse 1, bidding questions) each followed by the simple response, “Nothing but the blood of Jesus,” the hymn’s basic refrain and namesake. This phrase also completes the full refrain, which frames each verse. As with a Litany of the Precious Blood, each line in the hymn extols a different virtue of the blood of Jesus.

Sung to the catchy tune PLAINFIELD, it evokes the simplicity of a sung litany, being easy to learn and sing without accompaniment, and well-suited to being sung call-and-response style. Significantly though, there’s a key difference in how “Nothing But The Blood of Jesus” and a Litany of the Precious Blood praise the blood of Jesus. The hymn speaks of Christ’s blood as an object (even if it is a powerful, eminently valuable one) in the third person only. But typically, a Litany of the Precious Blood directly addresses Jesus in his blood, speaking in the second person as shown in the excerpt above.

This difference is rooted in understanding the blood of Jesus through a sacramental, Eucharistic lens. In this frame, the Blood of Jesus is shed for us not merely on our behalf. It is also poured out as a gift to us for us to partake in. Beyond being blood in the bare literal sense, it is Jesus’s very own divine and incarnate life, flowing to free and heal us from sin and the brokenness of this world, and to nourish us as his Body on earth in direct communion with his own self. Here, the Blood of Jesus is not merely a powerful object or force, but the Real Presence of Christ himself: to welcome and be welcomed by, to know and be loved by, and to have our lives transformed by.

“Nothing But The Blood of Jesus,” being authored by a Baptist, is not written with this sacramental, Eucharistic frame in mind. The main focus is specifically on the blood of Jesus having a sacrificial function in its being shed on the Cross. In a sense, the “blood” is also a metonym for Christ’s sacrifice, most likely understood according to contemporary Baptist understandings of the Atonement. Of course, the Litany of the Precious Blood also has sacrificial language, but its Eucharistic aspects (which the hymn lacks) also frame it more expansively.

Despite working out of this narrower emphasis, the hymn’s focus on Jesus’s blood as a substance having active power worth extolling lends striking resemblance to a Litany of the Precious Blood. This is an invitation to reimagine the hymn and its existing beauty in an even deeper, richer, and expanded way. For example, I wonder what it could look like for someone more creatively and lyrically inclined to write additional verses to the hymn which more closely reflect the sacramental flavor of a Litany of the Precious Blood.

I still do have some mixed feelings about “Nothing but the Blood of Jesus” as it is. In any case, I don’t know when I’ll hear it sung again. But when I do, I will hear it through a sacramental lens, with all of its vivid imagery enriching that of the hymn. I will see the image of the Pelican in Her Piety feeding her chicks, of a mother nursing her child, and even St. Catherine of Siena’s strange vision of drinking from Jesus’s side. I’ll even see the clear and refreshing sap flowing from a freshly-tapped maple tree in late winter. I will see those whom I visited near the end of their earthly life, remembering how they received the chalice (or spoon) from me with hope, yearning, and confidence on their tired faces. And I will see the Lamb of God pouring out life, forgiveness, and healing at the heavenly banquet; nourishing me now as he always has, and always will.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

(1) Ira Sankey, “Nothing but the blood of Jesus,” My Life and the Story of the Gospel Hymns (Philadelphia: Sunday School Times Co., 1907), 333. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/mylifeandthestor00sankuoft/page/332/mode/2up.

(2) Gavitt, L. N., Saint Augustine’s prayer book: A book of devotion for members of the Episcopal Church, Revised edition. (West Park: Holy Cross Publications, 1967), 289-292.