PRAYING COMPLINE THROUGH OUR ANXIETY

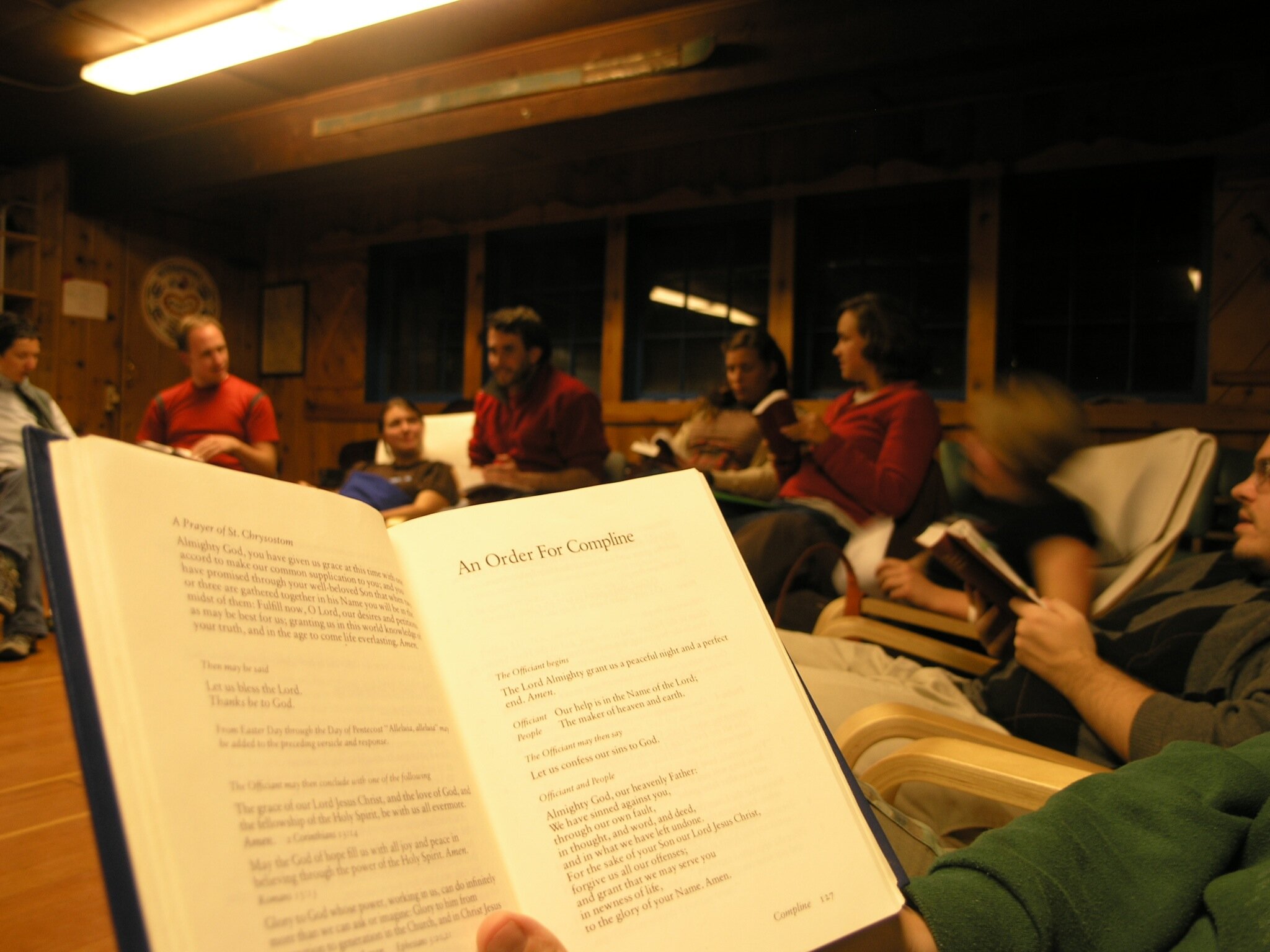

Photo by /profmeg/ on Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

If you’re like me, you’ve been spending more time than usual on your phone this past week. Yet as I scroll through my social media profiles, I don’t feel the connection I long for during this time of social distancing. Instead of feeling comforted by the nearness of others, I am grieved by the panic, loss, fear, and death we are feeling on a global scale. Alongside overwhelming statistics on COVID-19, my timeline is filled with political name-calling, heartbreaking stories of miscarriage, racist finger pointing, unexpected accidents, cancer diagnoses, and natural disasters wreaking havoc on communities.

Our cultural moment is consumed by fear and death. The outbreak of a global pandemic has radically affected our future, both near and distant. We are uncertain. We need food, yet shelves are empty. We need medicine, but there is none available. Where joy has ceased, death has abounded.

This cultural moment of death is not only physical, but also social. It is manifested in our social isolation, in lack of community, and in our inability to escape anxiety. It is exacerbated through a political divide that, even amidst a national crisis, cannot be mended. This social death has also deeply impacted religious communities around the world. Christians of all denominations and traditions are learning an “indefinite normal” as services move to online platforms. Liturgical denominations are seeking alternative ways to nourish the Body of Christ through both word and sacrament. Evangelicals are discerning what publicly sharing the Christian gospel can look like in this time. Muslim communities around the world are wrestling with heavy theological questions as well, such as how to practice Jumu'ah (Friday) prayer while mosques have closed and how they will practice Ramadan in their communities.

The Rector of Immanuel Anglican Church in Chicago opened up their first online broadcast by lightheartedly commenting, “you know there is a global pandemic when Anglicans start livestreaming their service.” While said in jest, it expresses a deeper truth (and lament) for this moment. This is different; or even more, this isn’t how it is supposed to be. Truly, this is a season of Lent and Eastertide that no Christian expected for 2020. As Christians, the physical matters; location and place and body are not secondary to the spiritual. While virtual gatherings may be the greatest act of loving our neighbors, it does not lessen the longing we have to gather together as the Body of Christ, especially on Easter Sunday.

In our uncertainty and unknowing, Christians around the world have asked the important question, “How then, shall we pray?”

For Episcopalians and other sacramental denominations, liturgy offers an answer. The very nature of written liturgy is to mark the highs and lows of our life – life and death, eucharist and baptism, confession and reconciliation. In this low season, both past and present liturgy offer daily practices, sacred rites, that make the Christian faith tangible in the life of the believer every day of the week. In this way, written liturgy ties the modern church to the church across time as we look to the written prayers of faithful Christians who have gone before us in times of rejoicing and of mourning, confessing their sins to God, offering thanksgiving, and petitioning God for his mercy to come upon us in times of blessing and trouble.

In my own life, COVID-19 has only been the capstone to a lasting season of anxiety that has affected not only my studies, but my spiritual life. It has been a long few months of depending on the Lord’s providence for the simplest things. In this season, I have held close to the liturgy of the ancient church, often reciting simple collects, antiphons, and psalms. I have also utilized modern liturgy which introduces new vernacular and modern cultural context.

One prayer I have turned to in this season of isolation and anxiety is the order for Compline, an evening liturgy found in the Book of Common Prayer. While commonly read in a small group, this prayer may also be read as an individual devotion. I have focused my own meditation on the antiphon of this prayer: “Guide us waking, O Lord, and guard us sleeping; that awake we may watch with Christ, and asleep we may rest in peace.” This humble petition is repeated towards the end of the liturgy, calling upon the Lord’s presence in both our outward actions and inward well-being as believers.

This antiphon is timely for Christians in our cultural moment. Fear and anxiety drive us inward, our inclination is self-preservation and comfort. Without realizing, we have stocked our cabinets and linen closets while our neighbors cannot find food at the grocery store. We sleep in and watch our church service from our couch while our neighbors are spiritually starving, desperate for a hope this world cannot offer. We cross our fingers for a magical check in the mail helping us in this time, yet we forget thousands of undocumented immigrants have no income and no hope for help from those who hold our nation’s wealth.

In this time I pray “Guide us waking, O Lord, that awake we may watch with Christ.”

A wise professor once told me, “when we desire to see the work of the Holy Spirit in our lives we must sleep, for it is the path of least resistance for the Holy Spirit to work in our hearts. So be alert!” Anyone who has experienced anxiety knows that it is not only psychological, but also somatic. Anxiety is a bodily experience just as much as it is mental. It steals our rest, our ease, our comfort, our joy, and even our health. Exacerbating our anxiety is the silence, the solitude of social distance. There is no physical voice to counter the voice of fear inside of us. We crave rest, yet it will not come because we cannot endure the vulnerability of complete passivity to the forces around us and within us.

It is in the depths of our depravity that we call upon Christ to give us rest and to guard us from the Enemy in our most vulnerable state. “Guard us sleeping, O Lord, that we may rest in peace.”

In these examples, I write collectively (we/us), yet I reflect on them personally (I/me). This is why I have held tight to this antiphon, pleading to the Lord for help to look beyond my own needs and watch with Christ and also comfort me in my anxiety, fear, hopelessness, isolation, and even depression. The order of Compline does not negate our experience or call us to ignore the true and honest emotions we feel in this moment. Instead, it offers us language to plead to the Lord in the very depths of our pain and longing.

Like the Psalmist, many cry “How long, O Lord?” (Psalm 13) and like Job, many lament “If I summoned him and he answered me, I do not believe he would listen to my voice.” (Job 9:16). It is in this time that the Church, the Body of Christ, may be a beacon of hope to the world, proclaiming the Good News that Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8).The antiphon to the closing canticle of Compline draws us out of our inward-bent imagination and offers us eyes to see those around us who are in need. It also offers us peace, calling on the protection and regard of the triune God in our helpless estate.

The order for Compline contains no special words, nor is it an immediate cure for our inward anxiety or the global pandemic sweeping our world. In fact, it is really a quite simple prayer. Like all liturgy, it is written to refocus our minds on Christ and to offer all our devotion to the triune God. It leads us to vocally entreat God for guidance when we are prone to our own desires. These long-said words are a timely petition to the Lord in this global crisis. May the Lord, in his mercy, hear our prayer.

O God, make speed to save us.

O Lord, make haste to help us.