GOD IS A NEGRO: WHAT THE BLACK CHURCH’S POLITICAL THEOLOGY CAN TEACH US

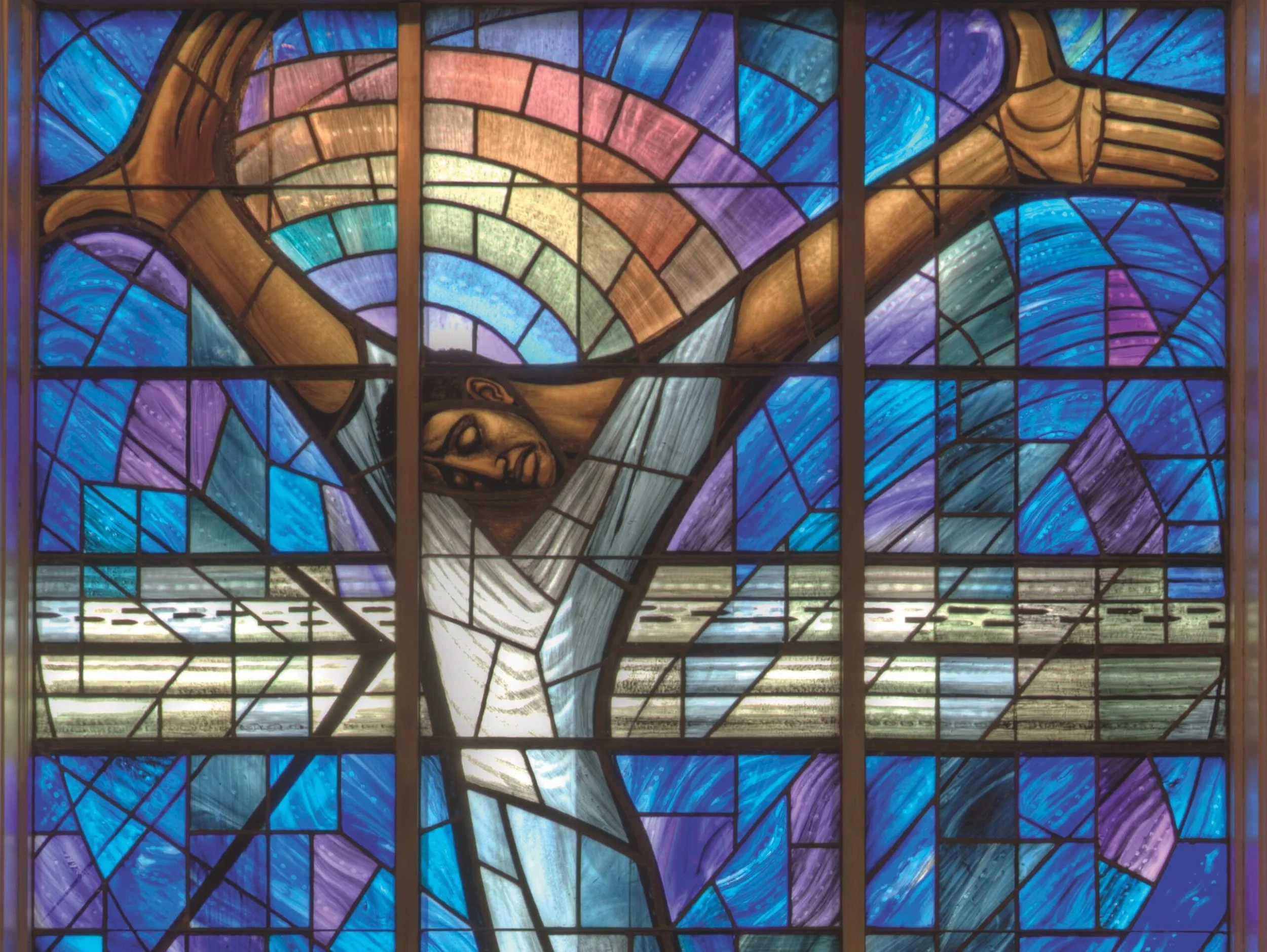

Stained glass designed by John Petts given to 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL

In a sermon published in an 1898 edition of the Pan-Africanist paper, Voice of Mission, the Right Reverend Henry McNeal Turner, a Bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a longtime Black nationalist, a former Georgia state legislator, and Union army chaplain during the Civil War, wrote, “We have as much right biblically and otherwise to believe that God is a Negro…We had rather be an atheist and believe in no God or a pantheist and believe all nature is God than to believe in the personality of a God and not believe that He is Negro.”[1]

At the fever pitch of what was, according to Black historian Rayford Logan, already “the Nadir” of American white supremacy and Jim Crow, after the devastating Plessy V. Ferguson Supreme Court decision which rendered Black America a “separate but equal” facet of American life, and as a wave of white terrorism against Black lives permeated the south, such a profound statement was revolutionary. And yet, Bishop Turner, in describing God as a Negro, remained not only consistent with his own personal convictions for the advancement of his race, but was continuing in a century-old theo-political tradition of resistance in thought, word, and deed, by the prophetic African American Church. Turner’s words are thus best understood not as an anomaly, but as a norm of Black political theology—God is a Negro.

Decades after his death, Turner’s theological statement would continue to serve as a foundation for Black theologians down through the decades. Howard Thurman, in his book Jesus and the Disinherited, articulated a liberal, social-gospel-oriented view of a historical Jesus of Nazareth dwelling among the oppressed Jews under Roman occupation. James Hal Cone, the father of Black Liberation Theology argued in Black Theology & Black Power that God was Black, and that Christ's message to the twentieth Century was Black power. Later Womanist theologians such as Delores Williams, Kelly Brown-Douglas, and M. Shawn Copeland, identify God with the lives of Black women, so often ignored or marginalized by their theological predecessors.

Of course, these theologians of the Black prophetic tradition are hardly monolithic in their Christianity and theology, but they all nonetheless represent a long tradition of resisting America’s long rendezvous with racial capitalism and the fascism it bears. They also have all constructed an alternative vision for Christian theology and the role of the church in America. In this time of rising fascism, we must explore this resistant and alternative vision, not so that we might seek refuge in an overly romanticized (and thoroughly contrusted) idyllic past, but so that we might construct a theo-political vision for our times, filled with the urgency and fierceness of the Spirit’s call to us.

A Defiant History

Though it should go without saying, African Americans, from the formation of the United States to the present, have never experienced their country as a true democracy. Though it is somewhat en vogue to suggest that the current wave of Christofascism infecting every aspect of the body politic is somehow a new phenomenon that unfortunately befell us in either 2016 with Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign and election, or the reactionary Moral Majority movement of the 1970s and 80s, for Black people, there is no novelty to the current moment, except perhaps in its speed of implementation.

From the atrocities of chattel slavery, to the subsequent Jim Crow era, the “benign neglect” policies of the 1960s and 70s, the Reagan and Clinton administration’s assault on Black urban America through racist drug enforcement and discriminatory welfare restrictions, and the current militarization of police in and against Black communities, every level of United States polity, from municipalities, counties, and states to the federal government, has, with few notable exceptions, used the might of its power to govern African Americans through violence and fear. Having spent over half of the first part of our existence on this land rendered three-fifths human and the latter portions a second class citizenry with tentative rights and freedoms, there is no conceivable denial that Black people have predominantly experienced the United States as governed by at least Herrenvolk democracy (to their exclusion) if not full on racial fascism.

Through our troubled and resilient history, however, the Black prophetic tradition within the African American Church has provided much needed relief, freedom, and hope to a denied people, seeking the affirmation of their humanity and dignity in the God who has been made known to us in Jesus Christ, the God who said “I am the good shepherd; the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep.” Indeed, Jesus was a “rock in a weary land” for a weary people, their comfort in times of trouble. The love of Christ and His presence among those who suffered and were heavy laden enabled African Americans not only to worship on Sundays, but to transform the church into a place of belonging, a staple of their communities where activism met faith and resistance was holy.

Their ministers and clergy used the pulpit to preach the Gospel as inseparable from social and political liberation, and some even sought public office, such as the first African American to serve in the Senate, the Rev. Hiram Rhodes Revels of Mississippi, who was a pastor in the historic African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), itself the first Black Christian denomination in the United States. Within our own Episcopal Church, a majority white institution since its inception, prophetic leaders such as the Rev. Absalom Jones, the Rev. Peter Williams Jr., the Rev. Alexander Crummel, and, much later, the groundbreaking Rev. Pauli Murray, stood as consistent activists, both within and beyond the Church for the Black freedom struggle. Therefore, for African American Christians, questions of the “religious” and the “political” variety remained unseparated; faith gave way to political resistance and political resistance was the embodiment of faith.

But if the Black Church was solace for Black people, it was invisible to the wider world. Indeed, Black Church scholars and historians call the Black Church during the period of slavery the “Invisible Institution,”[2] an era in which the slave-owning plantation class outlawed Christian worship among the enslaved without a white person present so as to not “excite them to rebellion.” But we must ask of the “Invisible Institution,” as the acclaimed author Toni Morrison did of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” invisible to whom? Who, both in the nineteenth century and in the present age, has the authority to determine what theology or way of being Christian is “seen and unseen?” This is both a structural and political question as well as a theological one, because how we answer it speaks volumes of how we understand God, people, the Christian faith and the role of the Church.

Toward A Visible Institution

If those of us who are Christian and anti-fascist are to take this current moment of Christofascism seriously, we must take the African American prophetic tradition and its Church seriously as well. For some of us, it means awakening to its presence and a vision of a robust and multifaceted institution much larger than Gospel choirs and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This means that we must both comprehensively understand the history of the Black Church and Black theology without limiting it to that history. In fact, it does have something to teach us now, and we are seeing failures to learn playing out in real time.

This means recognizing that the current methods that most major Christian denominations are using to resist the Trump administration, in both word and deed, are startlingly bare and insufficient, still behaving as if God is a benevolent white liberal and not the Word made flesh in Black skin. It is simply not enough for churches to issue statements denouncing the lawlessness and brutality of this white nationalist White House, when so few of them had anything of substance to say about Mr. Biden’s war in Gaza and his own brutal migration policies. Words are not enough, and even the words being chosen “urging” this administration to “show mercy” to migrants, for example, reveal a remarkable tepidness that is unworthy of the cross Christ calls us to bear in following him.

Furthermore, the bare-bones understanding of history that produces this tepidness, this awkward and unfocused resistance, is at the root of this problem. Contrary to its allure as a novel shiny object, there is, in fact, nothing new about the tactics or ideology of Christofascism in America, and there is certainly nothing new about the attempted unholy alliance of the Church and the State in “Christian Nationalism”—except perhaps that it is now being weaponized against other white people. It is not only present in gun-toting evangelical Christians who worship a god of white supremacy and death, mocking the Gospel and dishonor the LORD daily with their fawning admiration for Trumpism— it is also present in the naves of our own Episcopal cathedrals, adorned with American flags and the gravestones of dead presidents. It is present in the pews emblazoned with brass plaques bought and paid for by wealthy benefactors, some of whose wealth is multigenerational and likely linked to slavery and some newly acquired through exploitative labor practices and deregulation that disproportionately impact black and brown bodies. It is not only present in the shocking displays of pastors in the White House blessing and bestowing praise upon an administration that is kidnapping migrants and slashing Medicaid for the poor, it is also present in own National Cathedral inviting known war-criminal Henry Kissinger,[3] responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Southeast Asian civilians, to speak at a conference.

Our worship of whiteness, the structures of state and economic power, and our mirroring of this power in the inadequate ways in which we engage race, coloniality, class, and political engagement, is one of the Episcopal Church’s recurring sins. As a national church, we have done much work in talking about the issue of anti-Black racial oppression, but what has materially changed for Black Americans as the result of our discourse? Have we begun the long process of redistributing our church’s massive endowment to grassroots Black organizations doing mutual aid, rent strikes, and local political organizing, as some of our local dioceses have already done? Have we partnered with The Poor People’s Campaign as a denomination in the national struggle against poverty, mobilizing and funding clergy and lay leaders to do full-time local organizing as a ministry? Have we done sufficient work in ensuring that our internal processes, from our discernment process to Title IV, to the work of our diocesan councils and commissions on ministry, adequately reflect the racial justice we claim to be fighting for in the public sphere?

In all of these individual questions there is one that synchronizes them all, one that the church will be forced to answer directly: what does the gospel according to George Washington, Jefferson Davis, and Eli Lilley have to do with the Negro God? The simple answer is—nothing. Between the gospel of white supremacy and the Gospel of the Negro Christ, there is no relation, and it must be this acknowledgement, this seering reminder of our own complicity in anti-Blackness and the forces of racial capitalism, that guides our work as a national church.

Already, we have seen some para-church ministry funding of social advocacy organizations, we have seen priests join picket lines, and seminaries commit to reparations. These Gospel-centered and localized steps forward must be organized into an effort by the whole Church, similar to the work of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in the Civil Rights Movement, which combined local Black Church participation with mass mobilization, civil disobedience, and policy advocacy in advancing the Black freedom struggle and an end to poverty and war.[4] More than any other major social movement in American history, the African American Church’s foundational role in the SCLC reveals to us the power in numbers, and the success of radical movements that organize collectively, rather than individually. Learning from their successes and failures as a denomination is what it means to follow Jesus Christ in the twenty-first century.

And this is the raison d’etre of it all: we commit to this holy labor because we follow the risen, Black Christ. We do not participate in this “revolution of values,”[5] in Dr. King’s words, to curry favor with liberal organizations or to turn the church into a glorified non-profit organization. Nor must we ever be so naive to assume that either major political party is in lockstep with the Gospel. Rather, our discipleship means that we are willing to organize its faithful to resist any and all political parties or state leadership that fails to “do justice” and “love mercy,” whether they be the Republicans in Washington dismantling the social safety net or Democrats in the urban cities criminalizing the unhoused (even as they count on their votes!).

If “God is a Negro,” as Bishop Turner said, this means, in the late James Cone’s words, that He is “where the oppressed are,”[6] and the church, the whole church, must be also. The Black Church, more than any organized group of Christians in the United States has modeled what this presence looks like, deeply imperfectly, and yet with great boldness, being “not ashamed of the Gospel”[7] in St. Paul’s words. The Invisible Institution needn’t be invisible any longer, and the test of its visibility in our eyes will be in our ability not to just commemorate or memorialize it, but to follow its example, all the way to the Cross.

[1] Turner, Henry McNeal. “God Is a Negro.” Miami University. Accessed June 17, 2025. https://sites.miamioh.edu/empire/files/2025/05/1898-Turner-God-Is-a-Negro.pdf.

[2] Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South. Updated ed. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2004.

[3] Sony, Ouch, and George Wright. “Henry Kissinger’s Cambodia Legacy of Bombs and Chaos.” BBC News, December 3, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-67582813.

[4] “Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Accessed June 18, 2025. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/southern-christian-leadership-conference-sclc.

[5] Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break silence. Accessed June 18, 2025. http://www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil100/17.%20MLK%20Beyond%20Vietnam.pdf.

[6] Cone, James H. A Black Theology of Liberation: Twentieth Anniversary Edition. New York: Orbis Books, 1990.

[7] Romans 1:16