A STORY IN A CONFESSION

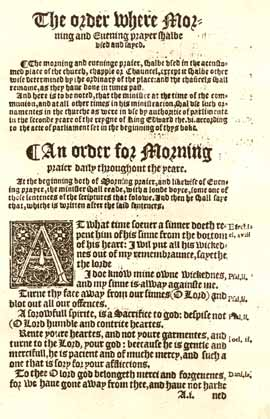

A confessional order from a BCP printed in 1559. Public domain.

There are, depending on how you count them, 7 different prayers of confession in the Book of Common Prayer. Some are for individuals, others are for groups. Some use anachronistic language, others use a more modern vocabulary. Some are reserved for special occasions or certain times of day, others are for daily or regular use. Beyond these specific prayers of confession and absolution, the BCP is full of penitential Psalms and prayers in which we admit our failures and shortcomings and seek God’s forgiveness and mercy. Out of all of these, one confession in particular has been living rent-free in my head, bubbling up every time I can’t find the words to pray, when can’t fall asleep at night, or when I just find my mind wandering:

Almighty and most merciful Father,

we have erred and strayed from thy ways like lost sheep,

we have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts,

we have offended against thy holy laws,

we have left undone those things which we ought to have done,

and we have done those things which we ought not to have done

[And there is no health in us].

But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us [miserable offenders],

spare thou those [O God,] who confess their faults,

restore thou those who are penitent,

according to thy promises declared unto mankind

in Christ Jesus our Lord;

and grant, O most merciful Father, for his sake,

that we may hereafter live a godly, righteous, and sober life,

to the glory of thy holy Name. Amen.

I love the comparison to “lost sheep,” the wonderfully alliterative phrase “devices and desires,” the almost poetic repetition of “ought” and “done,” and the description of our aspirational life as “godly, righteous, and sober,” but I think my favorite part of this prayer is its narrative structure. More than just listing our sins asking for God’s forgiveness, this confession tells a story of penitence, sorrow, forgiveness, restoration, and identity.

If you look up this prayer in your 1979 BCP—it can be found in Morning Prayer: Rite One (p. 41), Evening Prayer: Rite One (p. 62), and A Penitential Order: Rite One (p. 320)—you won’t find the bracketed portions included above. They were removed from the current version, and the confession is perfectly beautiful and good without them, but by going back to older versions that include these lines, the narrative structure becomes especially clear.

“we have erred and strayed from thy ways like lost sheep”

The first half of this prayer recounts our sins. Like someone easing into a lake, we are initially afraid to jump all the way into the cold waters of confession, and, by degree, we slowly become more honest with ourselves and with God about the severity of our condition. “Erred and strayed?” I mean, those are just goofs, really. Come on, God, we’re just your little “lost sheep!” Can you really blame us? I mean, you are our shepherd, after all.

“we have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts”

Sure, we’ve messed up, but our mistake isn’t necessarily what we’ve done, but the degree to which we’ve done it. We’re not saying that following the “devices and desires of our own hearts” is always wrong, just that we should have been focusing more on what God wanted for us.

“we have offended against thy holy laws”

Okay, yes, there’s no getting around it, God drew boundaries for us, and we’ve leapt right over them. Still though, there are so many rules, laws, regulations, commandments, etc, and if we’ve offended against God’s holy laws, at least maybe we’re still, through a secular lens, “good people?” Certainly we should be doing otherwise, but maybe at least our atheist friends might find our behavior, at worst, inconsistent with what we say we should be doing?

“we have left undone those things which we ought to have done”

Well, fine. We’ve really screwed it up. Maybe we can at least take some consolation in the fact that these are sins of omission. Yes, we absolutely should have done “those things which we ought to have done,” but at least we were just victims of our own moral inertia. It’s not like we actually went out of our way or made an effort to sin, …right?

“and we have done those things which we ought not to have done”

Oh. Right…

“[And there is no health in us]”

We finally hit rock bottom. If this line had been included and this confession updated to modern language, perhaps “health” would be rendered as “wholeness” instead. Not only have we failed to do what we should have done and done what we shouldn’t have done, we were never going to do otherwise. Of course we have erred and strayed, followed too much our own devices and desires, offended against God’s laws, and just generally done all the wrong things—it was basically inevitable. I mean, have you looked at us?

The sentence structure shifts here: every preceding line begins “we have,” but now we get “there is.” We have been the subject of each preceding clause, centering the prayer on ourselves. Now, as if we can no longer bear to look ourselves in the grammatical eyes and are finally realizing that putting ourselves first has been the problem all along, the subject shifts. It’s the syntactical equivalent of looking down at our feet in shame.

“But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us [miserable offenders]”

This is the turning point of the entire prayer. God crashes into our increasingly dire litany of “we” with a sudden pivot to “thou.” Pray this aloud a few times and you can’t help but notice the dramatic shift: “we… we… we… we… we… BUT THOU!”

The second half of the prayer is a reversal of the first. In a mirror image of our descent into sin, we see God restoring us to that health (or wholeness) which we cannot find in ourselves, but can always find in God. There are three parallel threads to follow through this part of the confession: how we refer to God, how we refer to ourselves, and what God is doing. Here, God is “O Lord,” emphasizing God’s position of power and authority and the seemingly vast distance above us “miserable offenders.” Perhaps a better modern equivalent would be “poor” or “pitiful sinners.” Having just recounted everything we’ve done wrong, this half of the prayer begins by locating us in a poor state, deep in our sin. Yet we are also “pitiable” in the positive sense as objects of divine compassion. Unlike the (potentially more familiar) confession typically used in Rite II, we haven’t even said “we are truly sorry and humbly repent.” Nevertheless, God’s mercy precedes our repentance! We are not climbing up out of these depths to find mercy; God is diving down to us to show us mercy right where we are and to drag us back out of this pit we have dug for ourselves.

“spare thou those [O God,] who confess their faults”

Now God is “O God.” There’s a degree less of distance here—as if we have gone from addressing someone as “Sir” or “Mr. ____” to using their name. We are “those who confess their faults.” We’re no longer just sinful, but have acknowledged our condition to God and to ourselves. God is sparing us the punishment for our sins; our sentence has been commuted.

“restore thou those who are penitent, according to thy promises declared unto mankind in Christ Jesus our Lord”

It’s not a direct address to God, but here we invoke Jesus’ name. We’ve gone from the distant, authoritative “O Lord” to the more familiar-but-generic “O God” to the more personal “[the Father of] Christ Jesus our Lord.” We have gone from sinning to acknowledging that sin to actually seeking forgiveness for those sins. God has not only had mercy on us and spared us, but has fully restored us to a right relationship with God.

“and grant, O most merciful Father, for his sake, that we may hereafter live a godly, righteous, and sober life, to the glory of thy holy Name. Amen”

“Most merciful Father” is not just a description of the intimacy and immutability of our relationship with God, but it’s also how the prayer began: “Almighty and most merciful Father.” We’ve come full circle, and our relationship with God is as it was before we went and tried to screw everything up. But where are we here? Where do we reference ourselves? “Most merciful Father” is a reference to God, but “Father” is a name that implies a relationship. God is our Father, which makes us God’s children. We don’t find our identity in relation to our faults, but in our relationship with God. This is also the first time in this half of the confession that we use the pronoun “we.” Unlike its earlier repetitions though, it’s not used to list off the ways we have strayed from the path, but to describe what God is doing in us as we walk more closely with God. And God is still doing more! We have been shown mercy, spared, restored to wholeness and God is still acting in us to sanctify us and bring us closer to God’s dream for us. A “godly, righteous, and sober [I like “thoughtful” or “attentive” as modern synonyms] life” lived for the glory of God’s holy Name is exactly the opposite of the life described in the first half of the prayer. The life God wants to help us live is the complete reversal of the one we confessed to living.

I think the reason this confession has stuck with me for so long is the journey we go on: admitting our sins, not only to God but to ourselves, being saved by God’s mercy, brought to true repentance and new life, recentering our true identity in God, and experiencing the wholeness we can only find in God. When we pray this confession, we are not only seeking God’s forgiveness, but telling ourselves a story about who we are as people dependent upon God’s mercy, forgiveness, and love. Maybe this confession works so well as part of the Daily Office because that is a story worth hearing over and over, every day and every night.