THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS: A CREATIVE TESTAMENT OF GROWTH, CONSERVATISM, AND THE VIA MEDIA - PART 2

A page of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Public domain.

Editor’s note: this is the second in a two-part series on the fascinating and beautiful Lindisfarne Gospels. Be sure to read last Monday’s article to get the whole story!

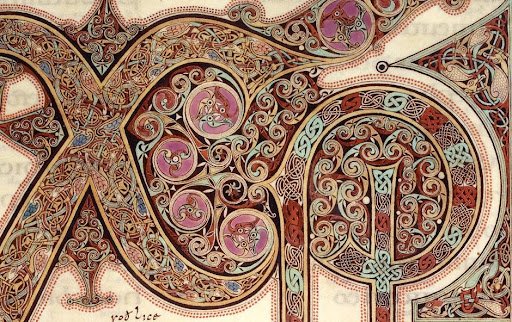

Throughout the history of the church, we find examples of the creative means by which the Gospel of Christ is shared with non-believers using existing culture and traditions. The Lindisfarne Gospels show us how one’s culture and one’s faith can become integrated, rather than supplanted or erased. For instance, the cross–the quintessential symbol of the Christian faith–has multiple uses in The Lindisfarne Gospels. The Celtic cross is known to have pre-Christian forms, especially as a “magical or protective symbol, guarding the entrances of sacred spaces.” (1) The cross is applied regularly to the pages of the Gospels in ways that are both pagan (protective) and Christian (redemptive) so that whenever the gospel was read, the congregation would associate the cross both with their heritage and their newfound faith. (2) The manuscripts made it much easier to guide non-believers through the gap between what they knew and what the missionary was teaching. These full-page crosses were meant to serve as protection both for the clergy and the book itself from “the evil of pagan practices.” (3) Missionaries would go into the depths of Britain armed only with faith and their missionary gospel book.

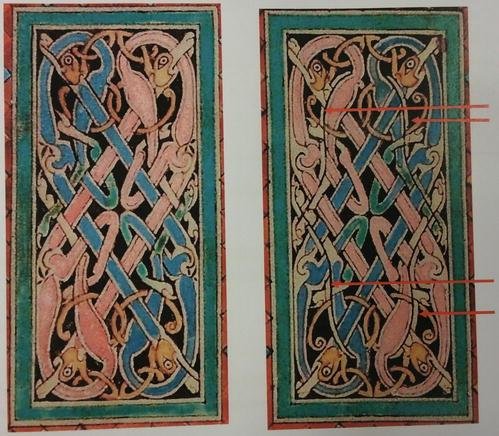

There are numerous examples of animals included in the ornament of The Lindisfarne Gospels. Each one of the creatures depicted was chosen intentionally. We know this from the repeated use of motifs across other illuminated manuscripts. Some are barely decipherable and others have been whimsically referred to as “dragon tangles.”

These zoomorphic images are almost entirely abstract and yet resemble animal forms. E.H. Gombrich suggests that “the ‘dragon tangle’ is a ‘protective animation,’ reflecting … the common practice of endowing artifacts with the potential to ward off evil.” (4) The scriptorium of Lindisfarne included folk magic and pre-Christian religious references in their most holy book as a record of their heritage.

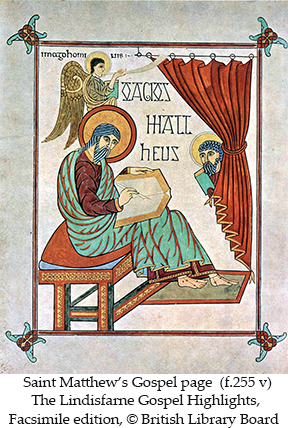

The Lindisfarne Gospels is a testament to the multiculturalism and partnership that was an effect of the monastery’s political importance and geographic location. Aside from preserving the Insular script that typographers today know as English minuscule or Insular half-uncial, the Gospels is a treasury of Pictish, Irish, and Anglo-Saxon motifs of plants, animals, humans, and linear carving from prehistoric standing stones. (5) The Lindisfarne manuscripts also indicate a familiarity with artistic and scholarly achievements across the Christian world. Its images of humans, and particularly the saints share many similarities to the linear figures of Coptic icons. (6) The Lindisfarne canon tables are graphically similar to those found in the Codex Fuldensis, written in southern Italy. These components of the Gospels’ canon tables, sourced from Italy and Palestine, were most likely brought to England from Rome by a Roman Catholic clergyperson. (7)

Other aspects of cross cultural inclusion are expressed in the Gospels. Carpet pages are full-page illustrations that resemble Persian woven fabrics, these carpet pages include design elements that show their inspiration from the Byzantine East.

Saint Matthew’s visage, the dot and circle ornament on his bench, and his attributed angel in profile are all visual clues that point to distant cultural influences of the Middle East, Africa, and western Asia. (8) The prevalent use of colored lead to paint the pages derives from sixth-century Byzantine illuminated manuscripts, which themselves were inspired by original Coptic paintings. This eastern influence most likely came to Lindisfarne by way of Egyptian monks fleeing the Arab invasions of the seventh century and is proof that they were not only welcomed into the community, but also engaged by the Lindisfarne scriptorium. (9) The effort represented by the multicultural influence on The Lindisfarne Gospels is incredible. The creators of this volume utilized resources and ideas from the farthest corners of the known world, which may be why The Lindisfarne Gospels is counted as one of the “most celebrated illuminated manuscripts in the world.” (10)

In the wake of the Synod of Whitby, efforts to portray Insular Northumbrian expression without ignoring Roman Catholic influences become apparent in the liturgical elements of The Lindisfarne Gospels. For instance, we can see similarities in the Insular Vulgate to that of southern Italian sources, the most obvious being the aforementioned Codex Fuldensis, establishing what is known as the “Italo-Northumbrian” family of manuscripts. (11) Later, the “Roman” Vulgate would be translated into Old English by adding a gloss in red ink to the original pages, which is the earliest existing version of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in the English language. (12) The “Canon tables” that serve as a concordance-lectionary system in The Lindisfarne Gospels is distinctly Roman, but their structure and ornament are Insular. (13) Writing with a script style that was specific to Insular Northumbria in “pure” Latin tells us how the religious practices of Insular Northumbrian Christianity not only survived the imposition of Roman Catholic culture but thrived because of it.

The Lindisfarne Gospels is a rich accounting of the turbulent centuries when the Synod of Whitby spelled the end of Lindisfarne’s traditional Christian heritage and the beginning of the Roman Catholic mission. The Lindisfarne Gospels has preserved the story of a people who were open-minded seekers of knowledge, adaptable conservers of the old ways, and quite often witty. The reforging of the Insular identity must have been tremendous work, but the amalgamation of multicultural ideals and religious practices through design and geometry can show modern humanity how a culture can make peace amidst conflict. The use of artistic expression as non-violent protest to cultural oppression or change is a long lasting and subtle tool for future generations to remember where they came from and why their faith is “written in the walls” of their holy places. The Lindisfarne Gospels is a testament to the power of humanity to be both conservative and progressive.

Guilmain 52

DeHamel, 40

Ibid

Ernst H. Gombrick, The Use of Order, Ithaca, 1979, 263

Brown, 288

Brown 287

McGurk,192

James Doan, Mediterranean Influences on Insular Manuscript Illumination. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 1982. 36

Francoise Henry, Irish Art in the Early Christian Period (to 800 AD), Ithaca, 1965

Eleanor Jackson, The Lindisfarne Gospels and its world, EBLJ, The British Library, 2022

Doan, 34

The Lindisfarne Gospels, EBLJ, The British Library, Jan 16, 2015

Brown, 304,