THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS: A CREATIVE TESTAMENT OF GROWTH, CONSERVATISM, AND THE VIA MEDIA - PART 1

A page of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Public domain.

45,500 years ago, a human being used ochre to paint three pigs chasing each other across a cave wall. This is the earliest known artistic expression crafted by human hands. (1) Throughout history, humans have used art to make sense of the world. In what is now southern Scotland and northern Britain, humans created books that used intricate patterns and motifs to make sense of science, mathematics, theology, and psychology. Often referred to as illuminated manuscripts, few are better known than The Lindisfarne Gospels. The Lindisfarne Gospels tells the story of a people forming their identity through the tools of design, religion, and multiculturalism, resulting in one of the greatest artistic masterpieces of Christian history. The Lindisfarne Gospels, as we will explore in this article, shows the modern Christian how ancient monastics, utilizing their unique regional art form, conserved and protected a rich heritage while simultaneously incorporating new ideas and culture from around the world.

The ancient kingdom of Northumbria straddled the border of modern England and Scotland, and was part of a larger Celtic culture that spanned from Ireland to Spain. In the summer of 625, Christianity came to this region, and within ten years a monk named Aiden arrived from the monastery at Iona to establish a new monastic community that would become Lindisfarne, a place renowned for its illuminated manuscripts. (2) Lindisfarne grew into small town built on a daily routine of prayer, meditation, manual labor, and illuminating Holy Scripture. The manuscripts and gospel books produced at and around Lindisfarne is a regional artistic expression that art historians label “Insular,” or “island” art. (3) This charmed life was disrupted in 664 CE by the Synod of Whitby, at which the conflict between Roman culture and Celtic culture came to a head. The King of Northumbria adopted Roman customs on the grounds that Jesus ordained St. Peter, the Bishops of Rome are St. Peter’s successors, and the Roman clergy were sent by the Bishop of Rome. Local Celtic kings and clergy refused to abandon their beliefs and practices to “bend the knee” to the authority and administration of the Roman Catholic Church, however. The resulting disputes made the region around Lindisfarne a focal point of political and religious struggle.

In this crucible of discontent and dispute, work on The Lindisfarne Gospels began. As the losing faction of the Synod of Whitby, the Northumbrian clergy responded by creating a “reliquary” of culture, art, and theology that is considered to be the climax of Insular gospel books and missionary codices. (4) Gospel books like The Lindisfarne Gospels and its smaller missionary versions were in high demand, as they were the primary teaching tool of Christian missionaries traveling to the northern tribes of Britain. The books’ script, decoration, and illustration were used as instructive tools to highlight the core teachings of Christ.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, begun by Bishop Eadfrith, contains the four gospels of Christ written in Saint Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, canon tables of scripture reference, the letters of Saint Jerome, and a record of Insular script and image. (5) Later, marks were added to make the book a lectionary, and a gloss was added to translate the Vulgate into Old English. The book is large and intended to be a showpiece set upon an altar or public space for all to see. (6) It would have been a magnificent sight in its original state– illuminated in gold and silver, bound in local woods, and covered in precious gemstones.

The subtext of the Gospels is astounding. Carefully crafted into the pages of The Lindisfarne Gospels are concepts and images that safeguard pre-Christian, pre-Roman, and Roman culture through a lens of multiculturalism that could speak to many Christians today. We will specifically consider three means by which the creators responded to the political and religious conflict of their time: the manner by which a typical page was produced, the inclusion of art forms both domestic and foreign, and the fusion of existent ecclesiology with the sudden influx of foreign language and liturgy.

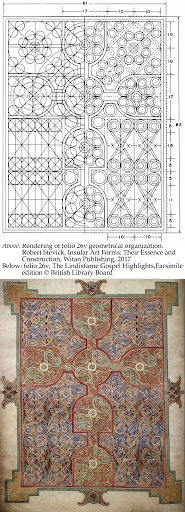

In most books on The Lindisfarne Gospels, the figures, structural details, and ornaments have been sorted, grouped, and removed from the larger composition, thus destroying the message of the whole. (7) If we critique elements of the pages only, we miss that each and every page of The Lindisfarne Gospels follows an intricate and inseparable system of structural design that is itself an ancient expression of Celtic culture. Precise measurements of the scrollwork and architectonic structure of pages were taken, and irregularities in measurements are on the scale of millimeters or less. (8) Although tools may have been used to measure and outline the structure of a page, the final work was done entirely by hand, and these slight discrepancies testify to the interfusion of mathematics and human expression.

The ratios which generate the intricate composition of Insular design could be set without numbers, mathematical equations, or algebra. This advanced geometry was passed down in Celtic cultures by word of mouth, using simple tools. (9) But when analyzed, the ratios are so specific that they can only be described as Pythagorean: 1:2, 2:√2, √2:√3, √3:√5. These proportions were constructed by compass work, using perfect circles and squares to make measurements and transfer them to other sections of the page. (10) This is called ad quadratum geometry, and has been used in Britain as early as 2750 BCE. (11)

The compositional structure of the pages, although architectonic at first glimpse, is not; instead, fully realized integrated forms direct the viewer continuously to the page as a whole. It is not a collection of organized images; the entire page is a single organism that continuously draws the viewer’s eye away from the individual elements and back to the entire composition. This partnership of ad quadratum geometry and artistic composition appears in other areas of Insular culture, and indeed all Celtic culture: we find organizational and proportional similarities in monuments like Stonehenge and Newgrange. Standing stones and temples throughout Britain use ad quadratum geometry to plan the structure’s construction using very specific Pythagorean ratios–the same ratios found in The Lindisfarne Gospels. (12) This geometry and planning reveals the presence of religion and science from both pre-Christian and Christian sources, hidden in plain sight and woven together so fully that it is hard to tell them apart. This brilliant conservation of existing tradition alongside the “new” concepts of Christianity is a lesson in the power of artistic expression to find common ground and bring together two seemingly conflicting ideologies in one space.

Julia Gonzales, World's oldest known cave painting discovered in Indonesia, UWIRE Text, ULOOP Inc., Jan. 16, 2021

Richard Gameson, The Lindisfarne Gospels: From Holy Island to Durham, Tired Millenium publishing, London, 2013. 12

Michelle P. Brown, The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality, and the Scribe, University of Toronto Press, Toronto and Buffalo, 2003

Christopher DeHamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts, Phaidon, London, 1994, 24

Gameson, 93

DeHamel, 30

Jacques Guilmain, The Geometry of the Cross-Carpet Pages in the Lindisfarne Gospels, Speculum vol 62, No 1, 1987, University of Chicago Press, 21

Guilmain 48

Guilmain 41

Rory Fonseca, Stonehenge: Aspects of Ad Quadratum Geometry, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Winter, 1995) 358

Fonseca, 358