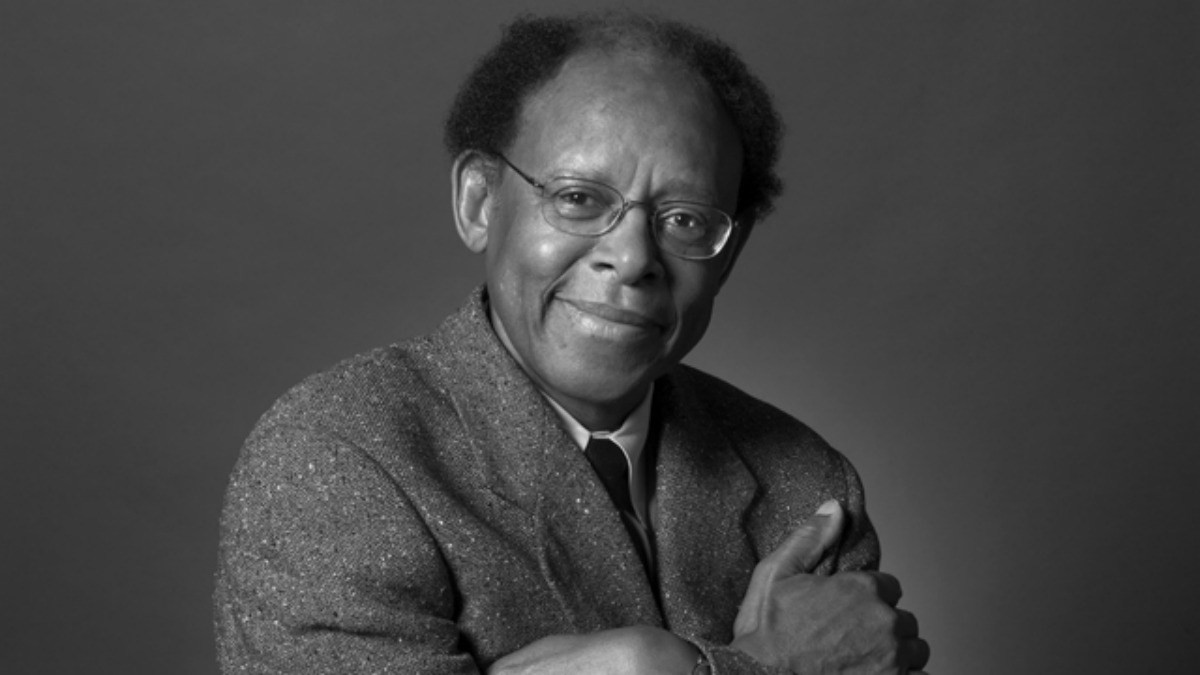

WHO IS JAMES CONE?

Public Domain.

I will never forget the first time I read James H. Cone’s revolutionary magnum opus “A Black Theology of Liberation” in the summer of 2021. After a prolonged period of spiritual death and deep struggles with understanding and accepting my Black and Queer identities, it was as if Cone’s words lit a fire in the depths of my soul and I came alive again. His bold declaration that white theology, which had dominated most of my theological formation up until that point, was not Christian at all but actually that of the Antichrist, gave me a sense of clarity and purpose that I had yet to experience. I soon came to realize that my experience with Cone’s work was not unique.

James Hal Cone was born in Fordyce, Arkansas, on August 5, 1938. He grew up in the segregated neighboring town of Bearden. Growing up with the music, spirituals, worship, prayer, dancing, singing and shouting of his African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church gave Cone his introduction to the unique and profound spiritual importance of Blackness. Thus, it came as no surprise that, in 1969, while teaching at Adrian College in Michigan, in the aftermath of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, the Black Power uprisings, and post-Civil Rights polarization on busing, affirmative action, and housing integration that Cone would find himself disillusioned and increasingly frustrated with the abstract nature of white theology.

While the church of his upbringing could talk at length about what “The Lord has done for me!” the white-dominated seminaries Cone found himself in as an adult could only offer long treatises of Eurocentric spiritual self-congratulation. They read Barth, Bultmann, Tillich, Aquinas, Niebuhr, and Augustine, as if these were the only figures that had anything at all to say about God and the Church. While each of these figures had earned their reputations as towering theologians, their theology was not primarily concerned with, nor their lives oriented around, the struggle for Black liberation.

Likewise, nowhere in the discourse of white-dominated seminaries was there any mention of the Black freedom struggle that was happening all over the country as Black people revolted against white oppression in Birmingham, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and Jackson. For white theologians, Christian theology was totally concerned with Eurocentric notions of morality and faith best typified by the evangelical preacher the Rev. Billy Graham. It is this theology, which views Christianity from the perspective of pious academic whites and charismatic white preachers talking endlessly about “saving souls,” that Cone would devote his entire life to destroying. After all, what did this theology ever produce for Black Americans but chattel slavery, Jim Crow, lynching, and mass death?

The palpable rage that Cone had at the treatment of his people as invisible and insignificant, coupled with the persistent and racist violence that continued to plague the country after King’s murder, burst forth in his 1969 theological debut, “Black Theology & Black Power”. In this book, Cone argued that not only was the Black Power movement of the late 1960s not in conflict with the Gospel, it was the Gospel. In the context of 20th century America, Jesus came not to make amends with white oppressors, nor did he come to sit in seminary halls and talk endlessly about Barth’s doctrine of election or Tillich’s views on the dynamics of faith. Rather, Christ came to destroy white racism, and to demonstrate God’s solidarity with the oppressed and the marginalized through militant Black Power. White America could either join Christ or the Anti-Christ, who, according to Cone, was the true object of worship for white Christians.

Published in 1970, Cone’s second book, A Black Theology of Liberation, was his elaborate and prophetic denunciation of White Christianity in America and his attempt at centering and celebrating the Black experience, both in the churches and in the streets. It was in this book, with his fierce eloquence and boldness on full display, that he asserted that “God is Black”, and that “Any theology that is indifferent to the theme of liberation is not Christian theology.” What did this mean? Was God literally Black? Did Jesus possess Black skin? The statement seemed bizarre, if not outright outlandish, in the eyes of white theologians. But Cone’s definition of theological Blackness left nothing up for interpretation. God was “Black” because God always identified with marginalized people and oppressed bodies as they struggled and yearned to be free of domination and control. Because in the Exodus, in the Prophets, and in the event of Christ Himself, God always identified with and dwelled with the “otherized” people of the world, God had to be Black in America!

Thus, God’s Blackness included Black people, Indigenous people, colonized people in the Global South, Jewish people, Women, poor people and, as Cone would state firmly many years later, LGBTQIA+ people. Wherever oppressed people are, God is there also.

The publishing of both Black Theology & Black Power and A Black Theology of Liberation earned Cone many accolades, including the appellate “Father of Black Theology,” but also opened him up to fierce criticism. Many white theologians critiqued Cone for being “divisive” and claimed that his theological claims did more to divide Blacks and whites than unite them. They were particularly outraged by Cone’s assertion that God was “Black”. In their minds, this was racism in the reverse order.

Black theologians, too, had their critiques of Cone. While Cone stated that Black experience was the source of Black Theology, the overwhelming majority of Cone’s cited sources for theology in both Black Theology & Black Power and A Black Theology of Liberation were white theologians and philosophers like Barth, Tillich, Niebuhr, and Camus. Thus, Black theologians stated his theology was “Black in name only.” Others critiqued Cone for putting such little emphasis on reconciliation as a central theme of the Gospel, still others critiqued him for his refusal to condemn violence as a mechanism of resistance to white racism.

But it was one critique in particular that would catch Cone’s attention. While he deeply respected the critique of Black male scholars for the over-representation of white theologians in his work, and worked diligently to correct that mistake, it was female Black theologians like Dr. Dolores Williams for whom Cone had the most respect. They critiqued Cone for his sexist language in his earlier works, charging him with failing to take into account Black female experiences of racism fused with misogyny as critical sources of theological reflection. They also resented Cone’s tepid acceptance of penal substitutionary atonement, which they believed justified of violence and subordination toward Black women.

Cone would address all of his critics, counter their arguments, implement some of their suggestions, and universalize his own thought in his most acclaimed book, God of the Oppressed, published in 1975. God of the Oppressed is Cone’s most detailed, confident, and universal work of theology. Cone had already defined “Blackness” as a universal social term, but now he felt called to examine what made Black Theology “Black” and “theological.” Thus, the sources and social conditions that produce theology are the primary focal points for Cone in God of the Oppressed.

For Cone, theology “arises out of a social and political context.” No one does theology “tabula rasa” and no theology is “apolitical” or “objective.” All theology originates from the context in which it is formed. Mainstream Western theology arises out of a context of European kingdoms and empires, Karl Barth’s theology arises out of a context of pre and post-War Germany, Reinhold Niebuhr’s theology arises out of a context of 20th Century America, and Black Theology arises out of a context of the Black experience from the 17th century to the present.

Black Theology must therefore function inseparably from its source: the Black experience of joy and suffering through white racism. As the Black experience encompassed the joys and sorrows of an oppressed people determined to obtain their freedom, the experience of God in Christ testified to the same reality. In other words, the historical experience of Blackness was a holy source for theology, because Jesus too, endured a “Black” experience through His birth, death and resurrection. God of the Oppressed thus served as, in Cone’s own words, a “final rebuke of white theology as a credible witness to the Gospel.” How could white theologians speak intelligently about God and be so divorced from God’s experience as a human in Jesus? How could they understand Jesus if they did not first understand the Black people in their midst?

To say that Cone’s theology shook the very foundations of American theology would be an understatement. Cone demonstrated that theology was not owned by white theologians, and not only were they not the only people to speak of God and the Church, but their talk of God and the Church was limited to their whiteness and their status as oppressors in an oppressive society. Only the marginalized could speak fully about who God was because God shared in who they were.

Cone’s final and most artistically eloquent work is The Cross and the Lynching Tree, published in 2011. Cone beautifully illustrates the haunting comparative nature of the cross of Jesus’ crucifixion and the American lynching tree using the Black literary imaginations of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. He also articulates a coherent theology of the cross that centers the cruciform nature of Christianity as the “terribly beautiful” symbol of God’s love for humankind. Finally, Cone ruthlessly critiques Reinhold Niebuhr, one of the most prominent 20th century theologians, for failing to theologically and politically understand and involve himself in the Black freedom struggle even as he condemned Hitler and the Nazi persecution of Jews.

In the fall of 2017, Cone, nearing his 80th birthday, finished his memoir Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody. The memoir focuses primarily on Cone’s life and theological formation, while also providing insightful commentary on Cone’s belief that theology comes from a social disposition; a disposition that can come in the form of biography.

Shortly after the book was finished, James Hal Cone died on April 28, 2018, at the age of 79. At his funeral service, held at the historic Riverside Church, the Rev. Dr. Raphael Warnock quoted Amos to describe Cone: “The earth could not bear his words.” A longtime student called Cone “The greatest theologian of the 20th century.”

What will history make of James Cone? What are we to take from his prophetic life and legacy? It would appear that, in these turbulent times of national upheaval, as white America continues to wash its collective hands of Black blood, that we remember Cone not only as a theologian, nor romanticize him as a saint, but honor him as a prophet who identified America’s sin and called its people to a life of repentance and liberation.