I, EZEKIEL

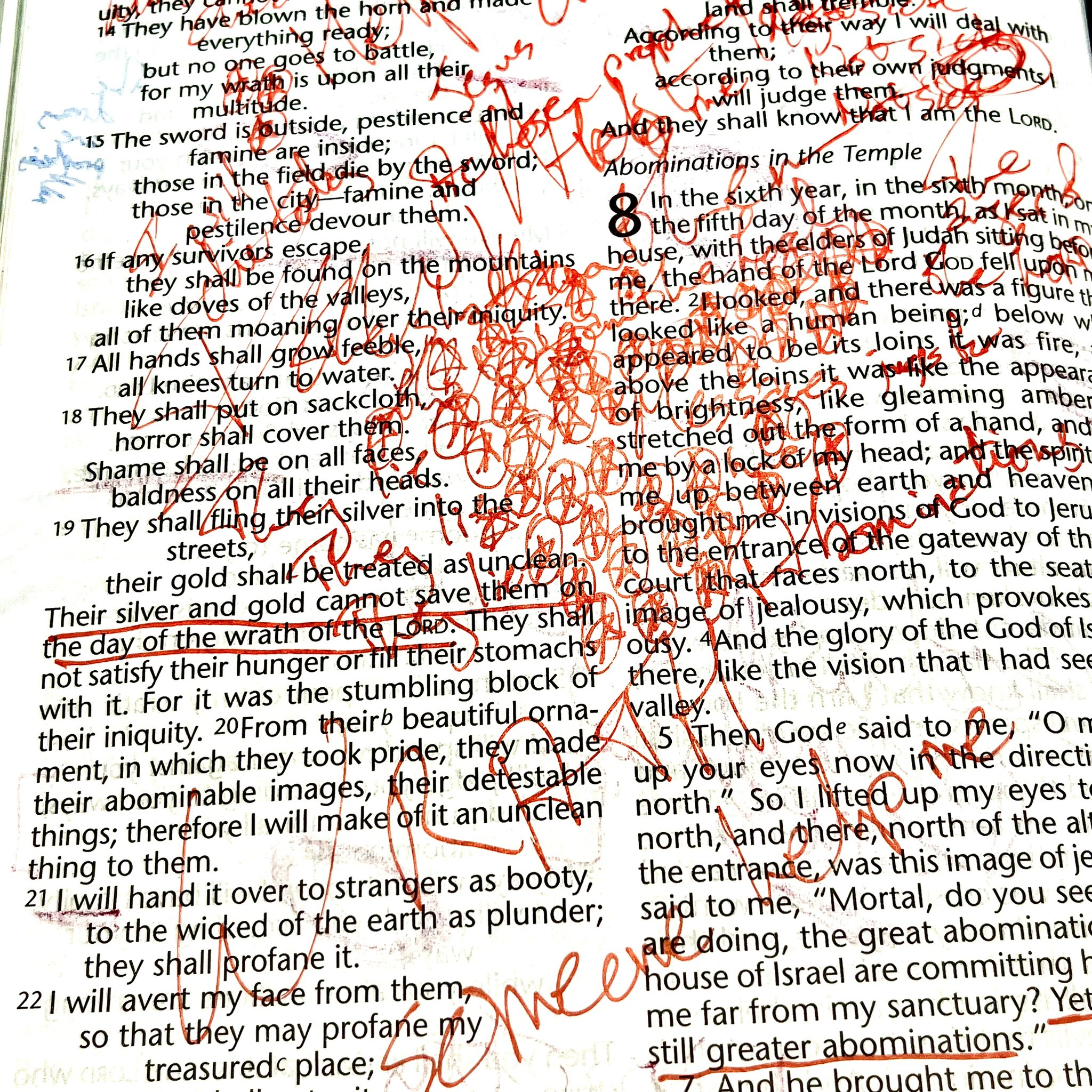

A photograph of the author's Bible.

At my sickest, I believed myself to be the reincarnation of the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel.

I spent hours poring over the prophet’s eponymous Old Testament text. Every word, every verse contained a message just for me.

I was a prophet. Chosen by God to carry a message of doom to the people. But first I had to prove myself and receive my prophetic word.

“Then God said to me, ‘Son of man, eat this scroll I am giving you and fill your stomach with it.’ So I ate it, and it tasted as sweet as honey in my mouth” (Ezekiel 3:3, NIV).

Just as God commanded, I tore pages out of my Bible and consumed them. And they filled me with a warmth I’ve only ever felt during the clearest moments of connection with the Divine.

Ezekiel the Schizophrenic?

More than any other Old Testament prophet, Ezekiel’s eccentric—at times bizarre—visions and behaviours have inspired posthumous speculation about his psychological state.

Catalepsy, seizures, hysteria—all of these and more have been proposed as after-the-fact diagnoses. But the one that resonates most closely with me is the diagnostic sign under which I (also?) travel: schizophrenia.

“Like the writings of schizophreniacs [sic],” wrote Edwin Broome, Jr., in an influential mid-century article for the Journal of Biblical Literature, “the writings of Ezekiel are difficult to follow: rules of ordinary logic simply do not apply.” (One hopes the present essay is an exception to this rule.) Stretches of catatonic “freezing” (Ezekiel 4:4-8); paranoid worries about being rejected by the people of Israel (e.g., Ezekiel 2:5-7); and, of course, the supernatural voices that he hears—all indicate that Ezekiel was on the schizophrenia spectrum, or so scholars like Broome would have us believe.

And maybe they’re right. But so what?

Does it matter one way or the other if Ezekiel was crazy? Does it matter if I am?

Discerning the Voice of God

I have heard the voice of God, clear as a summer’s day, commanding me to prophesy.

I have heard the voice of God, warm as a summer breeze, calling me to a life of reflection on God’s Word.

One of these is the result of dopamine imbalances in my brain. The other is the reason I went to seminary.

Only one of these is “real.” Only one of these “counts.”

***

As Christians, we are very good at subjecting the abnormal to discernment.

Women’s ordination, the inclusion of 2SLGBTQ+ people in the life of the Church, switching from in-person to digital worship—all these require intense and protracted prayer and debate. Because they’re unusual, or, at least, because they seem to be.

The commonplace passes without reflection. We don’t think about the flag at the altar rail; it’s always been there. Of course God called that cishet white man to ordained ministry; we can trust that God speaks to that kind of body.

There’s something idolatrous about our uncritical acceptance of the ordinary.

It’s not that the ordinary is necessarily bad. It’s that, as Paul Tillich defined idolatry, “something essentially conditioned is taken as unconditional, something essentially partial is boosted into universality, and something essentially finite is given infinite significance.”

We divinize the ordinary and demonize the extraordinary by uncritically assuming that God is present in what we know and absent in what we don’t.

And so, we accept that the person who feels a burning desire to undertake ordained ministry is hearing the voice of God. That’s how God speaks.

Whereas “obviously” the person who audibly hears the Divine voice cannot be trusted. God doesn’t speak to “us” that way. There’s nothing we can learn from “them.”

After all, they’re crazy.

***

It is ableist indeed to exclude schizophrenics from the ambit of God’s revelatory activities in the world. It also betrays a rather low view of God’s ability to make Godself known in and through the disabling experiences of this life.

That said, there is something qualitatively different about a schizophrenic episode and an instance of Divine self-disclosure, something that the former only simulates.

In Scripture, the Word of God is terrifying, incisive, and sometimes rejected—but it is never unclear. When God speaks, you know it is God speaking.

That’s what distinguishes the Voice of God from the voice my illness told me was of God.

In psychosis, you lose the ability to distinguish what is of the world from what is of your mind. Everything is real—the hallucinations and delusions all.

There’s the key difference. The Word of God is not real. Not because it is “false” or “non-existent.” But because it is not of this world, a thing among other things, like a stapler or a song. Nor is it of the mind, an idea among others, like theology or dinner plans. It exists in both but is not reducible to either.

And when you hear the Word, in whatever form it might take, that fact is clear.

The Word of God precedes and exceeds creation; it comes before, and it extends beyond. And when it enters into the created world, it rends reality apart: precisely because it is not a part of creation, it is what creates. Hence the frequent scriptural refrain of the heavens opening—that is to say, of reality tearing (in the Greek: schizo, the root of schizophrenia)—during visions of the eternal (e.g., Mark 1:10).

When God speaks, this world is shown to be partial. There is something else “out there” in the space beyond what we can normally see, hear, and touch. And knowledge of that fact overwhelms.

Perhaps that is why, when the angel appeared to Mary, it was with the words “Do not be afraid” (Luke 1:30). Fear is the natural response to revelation. And wonder.

The Schizophrenic Sublime

If God speaks to schizophrenics—as I am convinced God speaks to all God’s people—it is in spite of our schizophrenia. Much as God always speaks to people in spite of our creaturely limitations, whatever those may be. But there is nevertheless something about the experience of psychosis that offers unique insight into the ways God speaks to dis/abled bodies, something those who have never shared in that experience can only come to understand through the testimony of those of us who have.

This is not to romanticize psychosis.

There is nothing romantic about a schizophrenic episode. It’s a terrifying, disorienting ordeal.

But there is something sublime: an experience of beauty born of dread.

When you travel beyond the borders of reality and return again, what you’re left with is awe.

Awe at the fragility of the real. Awe at the vistas that resolve into view when reality shatters.

I experienced schizophrenia as the re-enchantment of the world. Angels and demons were everywhere, spiritual forces were at work in the smallest of happenings, God spoke to me as clearly as he did to the Old Testament prophets.

It was a frightening world to inhabit. But it was also beautiful in its marvels.

In psychosis, the mind simulates the inbreaking of another reality into this one that occurs in actuality during moments of Divine self-disclosure. Reality is shown to be “more than” what one previously thought. The veil between the real and the unreal is pierced, and things we can only imagine are revealed to us.

Those things aren’t “real,” of course. But that doesn’t mean the experience of encountering them has nothing to teach us.

Indeed, the schizophrenic sublime is such that those who have experienced psychosis know more fully—if still only approximately—what it is like to hear the Word of God than those who have not. Simply because we schizophrenics who have ventured to reality’s edge and returned again are experienced enough to know not to idolize the real.

We know better than to equate the empirical with the universal; to take what we can see, hear, and feel one day as the extent of what is. Our horizons are forever haunted by the advent of something more: another hallucination, another delusion, another reason to be paranoid.

Because reality is frail. Its bounds are porous. And if it is permeable, that is because reality isn’t all there is. There’s something else beyond.

As a Christian, I would call that something “God.”

Which is why Ezekiel the “crazy” prophet is a prophet nonetheless.

Even we schizophrenics have much to teach the Church.

This Is My Body, This My Schizophrenic Mind

Ezekiel’s consumption of the scroll is Eucharistic.

The scroll contained “words of lament and mourning and woe” (Ezekiel 2:10). But in a more substantial sense the scroll contained the Word, that which empowered Ezekiel to give voice to the prophetic revelations of God.

Depth psychology understands schizophrenia to be the inbreaking of the mind’s reality into the external world. Where schizophrenia breaks the boundary separating inner from outer reality, divine revelation breaks the boundary between the Creator and creation. Different breaks, but breaks all the same.

The latter one comes into focus most clearly in the Eucharist. Bread and wine become the body and blood of the Word incarnate. Through our consumption of these elements, we are united with the perfect revelation of God in Jesus Christ. “Assumed by Christ,” Kathryn Tanner explains in Jesus, Humanity, and the Trinity, “Christ becomes the subject of our acts in much the way the second Person of the Trinity is the subject of Jesus’ acts. Our acts are Christ’s acts, we can say Christ acts when we act, in so far as what we are and do comes by way of the power of Christ.” Creature and Creator come together in a non-competitive correspondence of action that empowers us to act beyond our limitations as fallen creation.

Transcendence and immanence intersect for our benefit.

***

When reality breaks, anything is possible. Angels can whisper divine secrets in our ears. The devil can walk in our midst. Something as simple as the play of shadows on the sidewalk can contain abiding personal significance.

It is the contingency of reality that we schizophrenics know firsthand. Nothing has to be the way it is; it can all change in a moment, for better and for worse.

When reality breaks, anything is possible. Bread and wine can become the body and blood of a crucified God. The Divine can walk in our midst. Prophets can announce the coming of the glory of the Lord. Sinners can be swept up in the fount of all holiness.

It is the contingency of reality that we Christians accept by faith. Nothing has to be the way it is. It is all sustained by the very hand of God. In a moment, one day, God will remake it for good.

And if schizophrenics have just one thing to teach the Church, it is that reality breaks all the time.

***

I am not a prophet. In my more lucid moments, that much at least is clear.

What I am is sick.

And that has made all the difference.